In the musical South Pacific, the song “You’ve got to be carefully taught” is meant to instruct that racism is not inborn; it must be learned:

You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear, You’ve got to be taught from year to year, It’s got to be drummed in your dear little ear—You’ve got to be carefully taught!

I wonder though, given that in-group favoritism1 and out-group disparagement2 are such commonly-noticed aspects of the human experience, whether in fact you’ve got to be carefully taught not to be a racist, as opposed to falling rather naturally into an all-too-common aspect of the human condition. We are all racism-prone until we learn otherwise.

The same thought occurs in relation to the issue of self-censorship on campus. Are we “natural” self-censors, always fearing the power of majority opinion and its force upon us? Do we need to be actively taught to express opinion more freely, especially when we find ourselves outside of our in-group?

“Private opinion” means opinion that we truly hold to ourselves. “Public opinion” (in this context) means that which we are willing to express to others.3 I believe that the norm we are concerned about – in a learning context like higher education – is that public and private opinion should be roughly equal; there should be no constraints on the expression of true (private) opinion. But the reality almost always seems to be less than that.

If self-censorship is a norm in many contexts – and possibly growing? – the question becomes: in learning and study environments where we hope that private opinion is expected to be roughly co-equal with public opinion, how can one be “carefully taught” toward liberal forms of interpersonal engagement?

Do we naturally self-censor?

As part of an ongoing research project this year, with two colleagues I have been gathering data about peoples’ “natural” tendency toward self-censorship. In 2005, Hayes, Glynn and Shanahan developed a survey instrument called the “Willingness to Self Censor Scale” (WTSC).4 We defined self-censorship as “the withholding of one’s true opinion from an audience perceived to disagree with that opinion.” We used survey items like “I tend to speak my opinion only around friends or other people that I trust.”

Since the scale was developed in 2005, it has been used numerous times by other researchers and in a variety of contexts. Most often it has been an independent variable predicting whether the trait is related to decisions people make about expressing opinion. We are in the process of meta-analyzing these relationships, most of which show some degree of the expected relation (i. e., that WTSC predicts self-censorship behaviors).

For now, though, I’m interested in WTSC merely as a descriptive indicator. In our original study, we found a mean WTSC of 2.5, using a 1-5 scale. The scale mid-point 3 represented the 75th percentile in our data, so about one quarter of our respondents were agreeing or strongly agreeing that they were self-censors.

Based on this, I’ll take 25% as a “background” rate of self-censorship that we might expect in any given situation. Some people, by their nature, will never be active opinion sharers, and we need not conclude that this is a bad thing.

As I look at the studies we’ve gathered that have used our scale, so far I conclude that this rate does not change much across studies, which is what we’d expect from a personality trait. From studies that used our original 5-point scale, the average WTSC is about 2.7. Although I can’t see the distribution of the measure in other studies, it seems reasonable that they also distribute in the way our data did, meaning that, again maybe something around a quarter of people have identified themselves as self-censors. Some studies used 7 scale points, others didn't use all the items that we used, but results are roughly similar. When I standardize them all to the 5-point scale, the mean is 2.64.

Is self-censorship always bad?

I recognize that there are reasons to remain silent in many given contexts. Politeness, a feeling that our opinion is not well-informed, or even strategic silence can be reasonable alternatives depending on the context. As Denzel Washington memorably noted in American Gangster, the “loudest one in the room is the weakest one in the room.”

Beyond these normal situations where we don’t always speak our mind, what we are more concerned with is self-censorship in situations where it is not thought to be ideal. Political discussions and universities are two places where we would agree, I hope, that it is desirable to have as low of a level of self-censorship as possible.

Also, if I were designing a new WTSC, I’d probably add a proviso to the instrument, which would be that people self-censor when their audience is perceived to disagree, and when they otherwise would have also wished to express an opinion. That might help eliminate the situations in which people stayed silent for any number of good reasons. But still, I think we currently have a very good and useable measure.

Is self-censorship getting worse?

Gibson and Sutherland5 made a good comparison of survey questions on the issue. They use a generic question about speaking your mind that goes back to the 50s. In the reproduced figure (below), I see their data as moving above “natural” levels certainly by 2013. That is, numbers in the 40s are enough to suggest that more than just the habitual self-censors are involved. The authors explain the change as being due to “affective polarization.” In other words, we hate each other more now. If that is the case, one could understand why we choose our words carefully.

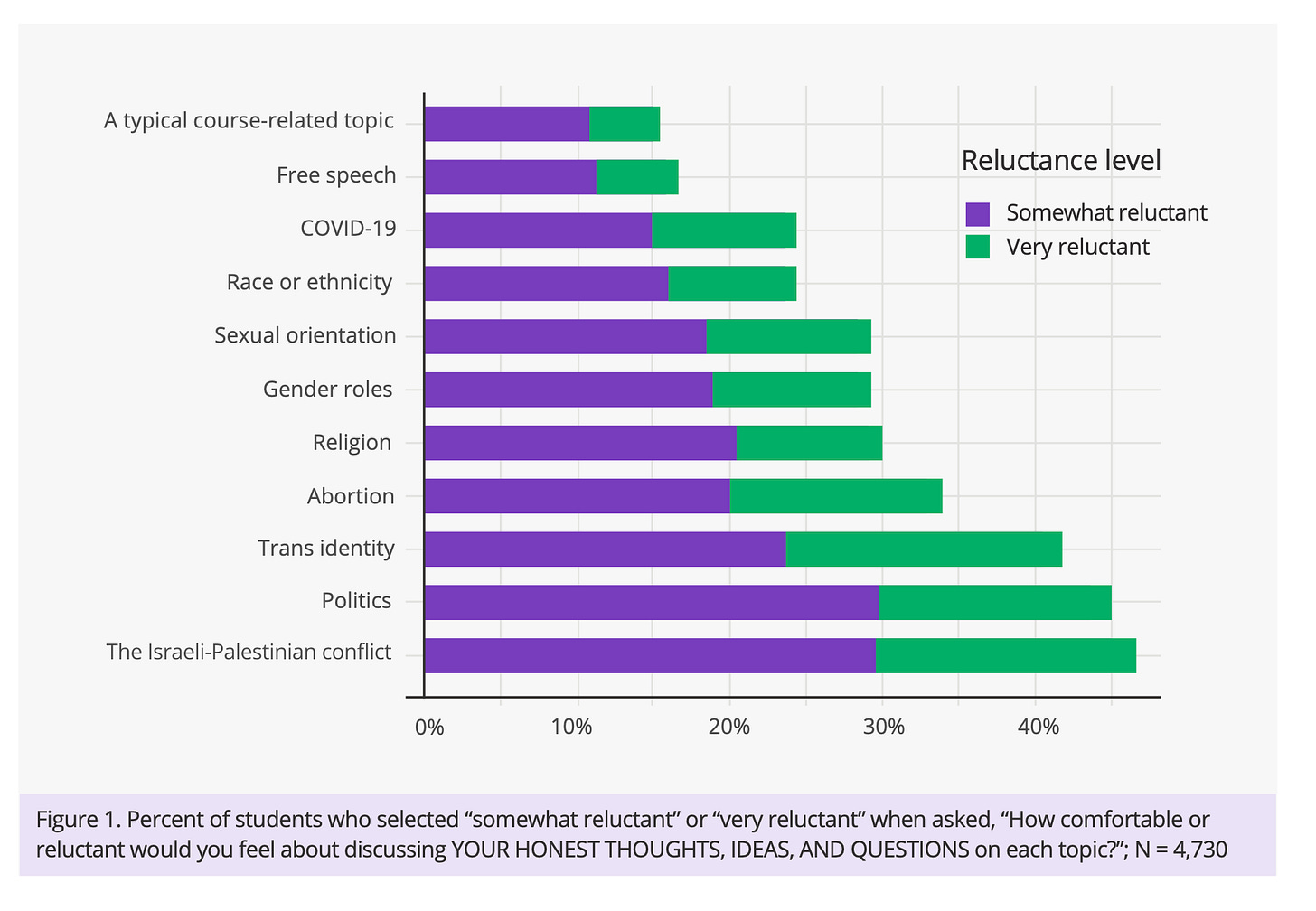

In colleges and universities, are things also this bad? Heterodox Academy’s recent data, compiled by Jones and Arnold,6 allow comparison across a number of issues. In the figure, topics like free speech or COVID-19 reflect lower, probably background levels of self-censorship. But clearly issues like abortion, trans identity, or Israel-Palestine incur higher levels of self-silencing. Troublingly, even “politics” itself looks like a third rail.

Beyond polarization

I started off as somewhat skeptical that self-censorship is an especially unusual problem now more than it used to be, but I think some of the descriptive data indicate cause for concern. It would be consistent with the idea that we are still immersed in a cancel culture, where both students and citizens hedge their bets by being silent when possible – especially on certain kinds of issues where “everyone knows” the dangers of speaking out.

Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann referred to a “quasi-statistical organ” that people have that lets them know when their opinion will be supported or not, and she also indicated a belief that the media played a role in helping that organ to be even more sensitive to opinion popularity. If she had known of today’s social media, she might have doubled down on her idea.

Still, Gibson and Sutherland’s explanation of self-censorship and polarization begs a question: can we dig deeper? Polarization means stronger “identity.” A 50-50 split along identity lines indicates a high possibility for disagreement, where everyone has an equal chance of encountering someone you disagree with. Also, the polarization has brought a now-obvious struggle for cultural power. If polarization means we have slipped more into identity contests, it suggests to me that we have slipped back into the state of nature where untaught behaviors like racism and self-censorship become more likely, along with the moral judgments that we make along with them. To get away from this, we have to be “carefully taught.”

Teaching silence

Current initiatives at universities toward viewpoint neutrality are obviously intended to foster an atmosphere where self-censorship is less likely. They are clearly a needed response to the dysfunctional fact that university speech might be more structured, restrained, and censored than speech in the everyday world.

However, they are structural remedies that can only be effective so far, without real reform in terms of what is being taught. Institutional neutrality itself says nothing about how disciplines will teach about issues of free expression, including the actual issue of neutrality itself, which many faculty will oppose. A position of neutrality will continue to protect those who are opposed to neutrality, including those who feel that universities should be ideological projects.

Worsening self-censorship, if it is a failure to teach, means that we need to look at doctrines that excuse problems of free expression, or even encourage it us to ignore such problems. We know the usual suspects here. Disciplines that should lead the way toward support for free communication – law, history, politics, journalism – are also those where one finds troubling concepts that give us a world where liberalism is a devil, where academic vanguards are necessary to lead us toward properly regulated and moderated forms of speech, and where ultimately information itself is labeled as true or false in accordance with the extent of its agreement with ideological concepts.

Here I’ll only mention one of those fields, journalism. In a previous post, I wrote about how journalism scholars at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication deal with a concept like “objectivity” only in the negative, as something indelibly stained by its relationship to whiteness or capitalism. And yet, in the same conference, many papers are dealing with how to communicate about “misinformation.” As I noted in that piece…

“…much journalism theory is steering away from objectivity, which is ironic if journalists are to play a role as fact-arbiters, especially as people trust journalists less and less. And, we know that vast swaths of the public are coming to believe that misinformation is basically part of an effort to sustain greater levels of control of information.”

None of this seems any better in light of brand-new Gallup numbers on trust in journalism, which have again reached record lows.7 Wouldn’t we be better off went back-to-basics with objectivity in our journalism education?

I do see reason for optimism, however. I did go back and look at the AEJ abstracts from 2022-2024 where the topic dealt with speech or free speech. True, there were some that seemed to be anxious to do away with objectivity.

Negative attitudes toward free speech

This paper argues that money corrupts the marketplace of ideas, and proposes a corrective to the problem...

Under existing First Amendment principles, it appears COVID-19 misinformation communicated by medical professionals may be protected.

Instead of accepting the conventional notion that regulation of student expression should be based on the marketplace of ideas theory, the paper proposes that student expression should be protected under the safety-valve theory, which would lead to an expansion of speech and press rights.

While the idea of freedom of speech and expression is a hallmark of major democracies, #MeToo demonstrates that it is uncomfortable with women’s voices.On the other hand, some of abstracts (some coming from AEJ’s law division), do still take a more positive attitude toward free speech.

Positive attitudes toward free speech

A survey of 224 students at a state university showed those who favored particular tenets of a campus speech code were prone to a fear of social isolation, which is part of SOS theory. The study suggests campus speech codes not only inhibit communication, but can impact the social psychology of students.

Freedom of speech is central to journalism and mass communication education. This study investigate how U.S. undergraduate faculty are teaching First Amendment and media law courses, using a national electronic survey distributed to 486 faculty via email. Free speech still has advocates on both sides of the culture debate. It retains a certain bi-directional appeal. Overall, I hope that journalism scholarship will follow (some) universities’ leads on institutional neutrality by rehabilitating the concept of objectivity in journalism.

Self-censureship

Can we imagine this year’s (2024-2025) self-censorship numbers getting better in colleges and universities? If institutional decisions toward viewpoint diversity make potential speakers feel that they are less likely to be punished – that they might lose scholarships, fellowships, jobs, etc. – then maybe there will be some effect. To the extent that universities punish their own (“self-censureship”) it works to the good to do less of it.

However, real education – making sure that people are “carefully taught” to respect freedom of expression – occurs at levels below the President’s office. If this year is to be a sea change for the flavor of free speech in education, it will have implied an impact of administrative policy on faculty activity that I am not normally used to seeing. But it’s a start…

Fu, F., Tarnita, C. E., Christakis, N. A., Wang, L., Rand, D. G., & Nowak, M. A. (2012). Evolution of in-group favoritism. Scientific Reports, 2(1), 460.

Ford, T. E., Richardson, K., & Petit, W. E. (2015). Disparagement humor and prejudice: Contemporary theory and research. Humor, 28(2), 171-186.

Kuran, T. (1990). Private and public preferences. Economics & Philosophy, 6(1), 1-26.

Hayes, A. F., Glynn, C. J., & Shanahan, J. (2005). Willingness to self-censor: A construct and measurement tool for public opinion research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 17(3), 298-323.

Gibson, J. L., & Sutherland, J. L. (2023). Keeping your mouth shut: Spiraling self-censorship in the United States. Political Science Quarterly, 138(3), 361-376.

https://heterodoxacademy.org/reports/reluctance-to-discuss-controversial-issues-on-campus-raw-numbers-from-the-2023-campus-expression-survey/

https://news.gallup.com/poll/512861/media-confidence-matches-2016-record-low.aspx