In June 2020 I was ready for a break. Getting through an academic semester – managing a college through COVID – was nothing but an extended day/night-long series of Zoom meetings. Frustrated parents, students, staff, colleagues. Some days I was the only person in our building.

The end of the semester still was high-concern about the virus. To be able to take a trip somewhere (anywhere), I told my wife I would pack the Jeep, mitigating any risk of COVID by traveling only to poorly-populated places.

I looked at maps and statistics to select places to visit that would be the least-populated in their respective states. On June 6, 2020 I drove southwest from Bloomington.

Illi-tucky

First stop was Cave-in-Rock, Illinois. It is, yes, a cave in a rock, on the Ohio River. Hardin County is Illinois’ least populated.

The cave looks to be a perfect location from which to have assaulted settlers that were rafting down the Ohio River toward the west. There are stories to this effect, but they can’t be confirmed.

I walked up to the cave. I didn’t go all the way in. I could see well enough inside for my own satisfaction.

This checked off my first least-populated county, but my other intention on this first leg was to get to Cairo, IL. With Huckleberry Finn on my mind, I thought it would be grand to stand at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi.

I went to looking out sharp for a light, and sort of singing to myself. By-and-by one showed. Jim sings out: “We’s safe, Huck, we’s safe! Jump up and crack yo’ heels! Dat’s de good ole Cairo at las’, I jis knows it!”

Alas, the real Cairo is destroyed. A long history of racial issues and tectonic economic transitions in river trade have made it a husk. I didn’t spend long looking for the confluence. Seeing what was around me, I judged it wise to perhaps not stop the car, nor to linger to take photos of the urban remains.

Little Egypt

Why is it called Cairo (pronounced Kair-ro)? The triangle at the bottom of Illinois is called “Little Egypt.” Some say it has to do with the feeling of a river delta. I’ve driven around the parts of it that are near the Wabash and Indiana. I find it a very interesting part of the country. I’m not sure whether it is the South, or the Midwest, or just its own thing.

Once I was in Old Shawneetown, where there is an river crossing, soon after the Ohio’s confluence with the Wabash. The town is almost entirely deserted, though it had been the site of the first state bank in Illinois. I climbed up the levee and looked at the river. There is a big saloon-type building there, which looks like it had hosted biker-oriented entertainments not too long ago.

I also saw this on the town common.

I have concocted various scenarios to explain this sight; none of them are too appealing.

Overall, though, everyone I’ve met in Little Egypt has been friendly and helpful. There are corn and bean fields, yes. There is coal, there are oil wells, and in some places the smell of gas drilling makes one kind of queasy. There’s a very narrow (some say haunted) wooden bridge from St. Francisville, IL that you can cross for two dollars. I started out from the Indiana side and instantly regretted it. But made it safely…

The sign at Grayville, IL tells you some of Little Egypt’s past, and of a future yet to fully materialize.

At the upper left is a torch; I’m not fully sure of its meaning. Middle is the Central Illinois Railroad. Upper right signifies Grayville’s oil production. Lower right must refer to the Buffalo Trace. And I’m guessing a prominent Grayville family home on the left.

Under the right conditions, Little Egypt is absolutely lovely.

The Deserted Ozarks

From the destruction of Cairo I headed across the delta of Missouri down into Arkansas. My goal was to get up into the Ozarks, without much thought of what I might find there. The least populated county in Artkansa is called Calhoun. It was off my general route, which was mainly oriented toward westing with a little bit of southing thrown in. So instead, I persisted across the northern tier of Arkansas counties.

I picked a hotel that was open in Mountain Home. Throughout the journey, I mainly stayed in places where a Hampton Inn was available. At that time, Hampton Inn was engaging in a room-bleaching program of Trumpian dimension. The rooms had doors tape-sealed with special logos, and the smell was enough to convince one that a COVID virus would have been killed many times over. Of course, we later learned that this was probably not necessary, but I would not have believed it in 2020.

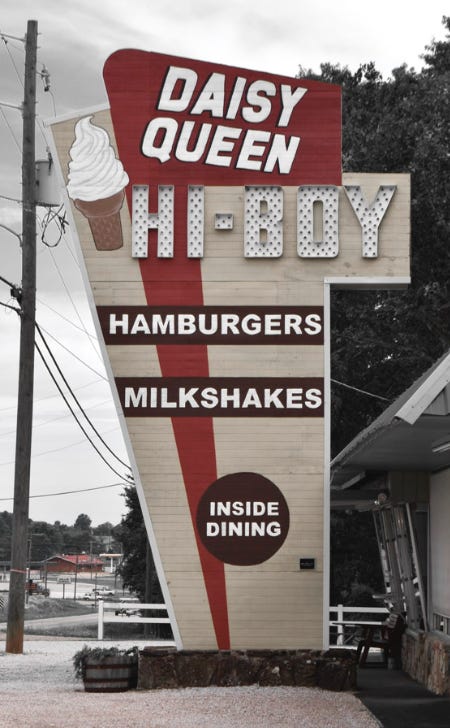

During my Ozark transit I saw almost no-one, and spoke to precisely no-one. I would have visited the “Daisy Queen” in Harrison, but it was closed. Foodwise, the journey was rough, as the options were mostly limited to gas stations.

I’d go back though; some pleasing vistas are available from the road that eventually takes you up to where the University of Arkansas is. I drove through it all to spend the night in Tulsa.

Friendlies

In Oklahoma, I knew that the least-populated county was Cimarron. It’s way out on the panhandle, and seemed an admirable destination if the goal was to see nobody. But the folks in Oklahoma turned out to be welcoming. I had no problem getting a hotel room; there were no issues with suspicion of people coming from out of state who could be bringing in the virus. Oklahoma had begun trying to get back to normal. Something was going on called the “Open Up and Recover Safely Plan,” of which I seemed to be a beneficiary.

Still, visiting major tourist attractions in OK was not my goal, nor am I sure what the actual attractions are. I spotted something on a map though, which was in the general direction of Cimarron, called the “Great Salt Plain.” I drove up toward the north and then headed to the plain, which did not disappoint.

It’s a wildlife refuge, and there is also lake next to it. The hot wind was sweeping down the plain in that day. I could have driven the Jeep out onto the flat, as one other group had done, but I did not want to get blown around by salt on the windshield. The lake was very red and choppy, a sea of blood raging in the wind. It’s about 1/4 as salty as the ocean.

In and out of Dodge

Before I could get out to Cimarron, I needed another Hampton Inn. The closest one was in Dodge City, KS. The name alone was enough to help me make my decision. In Dodge City there is a recreation of the “western town,” with all the various storefronts.

I walked into the town, which had very few visitors, but it was open. Kansas, every bit as much as Oklahoma, was getting back to business. After wandering around, a young man in a cowboy outfit came out, toting some shooting irons. I thought there might be a staged battle coming up. The crowd was sparse, though. As it happened, I ended up chatting with the guy about opportunities for young theater majors in Kansas, which are few.

After that, I strolled into the saloon and got a root beer. I played a few Western tunes on the piano to an empty room. The bartender took a picture.

With that, I considered a visit to Boot Hill, but I opted instead to hit the Santa Fe Trail, which would take me to Cimarron County. Along the way, you can pull over and look at the still-existing ruts from wagons on the old trail. I forgot to take a picture of them.

Geokryptophilia

There must be a word for people who are attracted to odd places on maps. “Cartophile” is as close I could get in English, so I have cobbled something together with Greek roots. Here’s Cimarron County on a map.

It has several advantages. First, I know that nobody I know will have gone there, nor will they ever. I can’t climb Mt. Everest, but I can go here. Second, I like driving through grasslands (although, by June, “grass” is optimistic). Finally, the road out of Boise City actually crosses ever so briefly through the corner of Texas, and the excitement of the TEXHOMEX monument (where the three states meet).

Grassland digression

One time I attended a conference in Fort Collins CO. On the day off, everyone headed up to look at the Rocky Mountains. I drove east instead, into the Great Plains. I headed for the Pawnee Grassland. After about two hours, I got to Stoneham, CO. This was the “town.”

Some settlers had tried things out there, but there was just very little water.

From Stoneham I headed north on CO 71. The road was everything I had hoped for: no other people. I did see two sights. One was a turn-off with a sign for a ranch that looked like a hippie-escape ranch compound (Manson alert), so I sped by that. Later, I did see what I think was an honest-to-god cowboy riding down into an arroyo after a stray heifer.

After reaching a height of land, I pulled off and stood around for about half an hour munching on peanuts. When I finally resumed my drive, I realized I was actually in Nebraska. So I just kept going, and circled back through Wyoming to get to the conference. Grasslands rule!

Bowling for dust

Some people would know Cimarron Country from this famous photo, by Arthur Rothstein. I doubt that it has done much for the county’s tourism profile.

Photographers like Rothstein really committed to being in rural America; I know it was impossible when they did these photos to whiz across the country like I did. In addition to the severe landscapes, they took photos of severe people, which was the point back then. Taking people-pictures makes me uneasy.

While in the town of Boise City, a deputy cruised by and checked me out briefly. Out of town a ways, I pulled over at an intersection. It’s a perfect place to flip a coin to decide which way to go.

I got out and stayed here about a half hour, eating my gas station sandwich. One guy passed me. He stopped and asked if I was OK.

Hostiles

The governor of New Mexico had decreed:

I drove across the northeast corner of New Mexico, happily having a mobile Zoom call with colleagues. I alerted them that I was approaching the Rocky Mountains, as I snapped a photo out the windshield.

I wasn't following each state’s COVID policy too closely, but I certainly didn’t plan to attend any large gatherings. When I arrived in the town of Cimarron, NM, the clerk at the gas station refused to speak to me. I got an uneasy, hostile feeling.

I went up the mountains and headed for Taos. The town was closed. There was no chance to visit any of the interesting sites. I checked into the Hotel Don Fernando, which was a collection of adobe-like structures with a roughly southwest look. In the lobby, the clerks were behind a redoubtable series of plexiglass barriers, around which the COVID virii would have to skirt to get at them. The only others there, registering ahead of me, were a team of about 15 hotshot firefighters, no doubt about to be dropped in to an active wildfire. So clearly they had reason to be traveling. Me, not so much. The clerks sent me to the very back of the resort, barely concealing their disdain for the Hoosier virus vector.

Not much was happening in town. It was the time of George Floyd, and a local communicator was out making a point.

So I was feeling ostracized in New Mexico. I will note that I was in fact self-isolating. Having come so far there was now finally something other to see than grass. In the Sand Dunes National Park, due north of Taos, there were people! Very spread out people, but a relative feeling of normalcy. Some folks climbed to the top of the dunes. I stayed at the bottom and watched the ants crawl up the hill.

From there, I ended up in Farmington, NM. This marked the extent of my westward progress. It became a base of operations for a day or two. It is well-situated for exploring lots of sparsely populated areas.

I realized, as I watched the local news, that my reasoning about northern NM was fine as population density was concerned, but that the counties of the four corners had the highest COVID rates of their states. Lots of people were getting COVID there. In fact, it later turned out that the Navajo had the highest per capita infection rate in the US. I would stress that I really met no people at all in the four corners, but there was the occasional person honking a horn at me, I think possibly in anger at my out-of-state license plate.

Population 0

A place that is famously depopulated is Chaco Canyon. It’s at the end of a very long gravel road. The folks that lived there left roughly one thousand years ago, and nobody is quite sure why. It is ironic that I actually encountered a brief traffic jam on the way in.

In Chaco Canyon itself, as ever, there were no other people. I suspect maybe a ranger was in the office, but I never saw anyone. There were no other tourists to spoil the effect of being in a place of great mystery. I could wander around from one ruin to the other, with no sense of how it could have been workable, given the overall dryness of the place. The stonework looks like it will last forever.

There were wonderful monuments.

Somehow, toward the end, my camera got on a funky special effects “miniature” setting. As I left Chaco, I saw some wild horses… I later learned that horses can have the virus, but they don’t get sick from it.

Periapsis

An elliptical orbit of a body, when it gets closest to the other body that it is orbiting, reaches “periapsis.” You swing around that thing and head back toward where you came from. For me, the body around which I was orbiting turned out to be Shiprock, a giant monadnock in the corner of NM.

Shiprock can be reached via more rough roads. There were miles of this…

I finally got close enough so that a zoom lens could fill the frame.

It was certainly the most majestic thing I had seen.

While looking at it, after a spell, I decided it was time to leave well enough alone and head home. I swung around and pointed my Jeep back eastward. I did cruise by the four corners out of curiosity, but it was guarded by sign that promised too much tourism.

You can go home again, in fact, you must…

I left Farmington and headed east across the northern tier of New Mexico. All of it is very beautiful. I got up over the Cumbres pass and into Colorado. I was pleased to be in a more settled farm community like Antonito, CO.

After more driving, I finally made it to a major interstate, leaving one last mountain behind. Some moisture was on the lens apparently…

In Pueblo, CO at another Hampton Inn, I realized that I might be having a medical situation. Not bad enough to kill me, but it could make driving 1000 miles back home dangerous. I needed some emergency room treatment, so I picked one of the local hospitals at random. It was called “St.Mary-Corwin.” There is no such saint. There is a guy called Corwin, and then the well-known St. Mary. Together they started the hospital.

I was worried that I did have COVID and that my trip was the whole reason. Guilt feelings… But my test was negative. They gave me some medicine and sent me on.

That morning, I was eating breakfast in my Jeep. A group of teens walked in front of me, and a handgun fell out of the jeans of one of them. It was calmly picked it up and they moved on.

I began driving across southern CO. It was as empty as anything I had seen, and I realized it still wasn’t safe to drive it solo. A flat tire could mean hours, days, months to wait for a car to pass by.

I did what any self-respecting lone cowboy riding the plains would do: I went back to where a cell signal was and called my wife.

She flew to Denver, where I met her and we drove peaceably back to Indiana.

An historic accomplishment

What caused the medical flareup? Now I think it was altitude. Nevertheless, upon return I did take steps to correct the situation once and for all, so I’d be able to make further adventures.

Given that we are all eventually headed toward a place where the people are few, it can be good to venture out to it occasionally, to listen to the questions that are raised.

I think I can confidently claim that no human has completed the specific journey that I made. Some of the places truly were the least populated, but most of them were not depopulated. Under better circumstances, it would have been nice to meet a few locals on the road, which is a reason to go back.

Oh, and to get another green chili cheeseburger in Farmington.