In 1990, I began teaching at Boston University, in the College of Communication (COM). I had a freshly minted PhD in communication, concentrating on studying the effects of media empirically. The undergrad students at BU were mostly interested in furthering their professional aims in the media field, and at that time there were no PhD students. I taught courses that were, therefore, not the primary interest of students, but of course the aim was to give them a college education as well as solid professional training.

One time early on my chair said that the students liked me, but they really didn’t know about my course content, and I had a vague sense that I could be in trouble when review time came around. But that never materialized. My teaching evaluations were OK, and since that time I never have heard of a tenure-line faculty member who got fired because of teaching.

Still, though, I wanted to show them that I could teach well, so whatever requests they made I usually obliged. One was whether I could teach a course called “Propaganda and Public Opinion.” I agreed. While my PhD research had lots to do with surveying and polling (public opinion), and with media effects (a kind of persuasion), I wasn’t so sure about the “propaganda” part. I had never formally studied it, and so I would be in the situation of staying one step ahead of the undergrads. As they often do, they obliged me by saying one step behind through the semester.

The first time I did the course (it was in the summer) the topics looked like this:

Syllabus CM 409 Public Opinion and Propaganda

This course investigates several related things:

1) the theory of "public opinion"; what is it, how is it formed, and with what impacts?

2) ways to research public opinion; how do we reliably comment about public opinion?

3) the theory of propaganda

4) historical instances of propaganda

5) the modern state of both propaganda and public opinion, and the politicized controversies surrounding it.

Readings included Propaganda by Jacques Ellul (which I already knew), books by Ian Kershaw on the rise of Nazism as a public opinion phenomenon, and various readings on how the idea of propaganda gave birth to my own field, the modern study of “media effects.”

Here’s how I teach it now, in a course called Public Opinion and Propaganda:

Week 1 What is public opinion?

Week 2 Persuasion: Classical and modern approaches

Week 3 Media effects on public opinion

Week 4 Public opinion and issues: Vaccination

Week 5 Public opinion and issues: Authoritarianism, right and left

Week 6 Measuring public opinion: Conducting a survey

Week 7 Midterm, prep and exam

Week 8 Propaganda, origins and definitions

Week 9 Literature and film of propaganda

Week 10 Propaganda in Nazi Germany

Week 11 Propaganda in Soviet Union

Week 12 Propaganda in China

Week 13 American propaganda

Week 14 “Disinformation” and “misinformation” now

Week 15 Survey Projects

Week 16 Propaganda Projects

I kept some of the readings I used at first, and broadened to include some items from literature and film. Overall I tried to be clear that propaganda occurs everywhere, from every side, at at all times, and also to make some effort to distinguish it as a specific kind of political persuasion apart from advertising, PR, and other such activities.

What I realized over the years is that I’m no expert in propaganda, a field which, by its very nature, reserves and conceals its expertise. If it’s working, you’re not supposed to know why. If you’re a practitioner and you know about it, surely you won’t tell others. From an ethical standpoint, one has to approach it as an outsider. Hopefully the instructor can glean enough crumbs to make a class illuminating, without drifting over to the dark side. Occasionally I would get questions about why we would teach propaganda to students, and of course I said that the goal was understanding, not practical instruction.

Perhaps the only way to truly function as an “expert” on propaganda, and to also serve ethically as an instructor, would be to be someone who had been on the inside, and then renounced it for the path of truth. A defector.

Cape Ann Days

In those days (early 90s) we lived in Rockport, MA. Rockport has a very good claim to be the most beautiful town in the US. It is a port on Cape Ann, which is perhaps better known for the commercial fishing hub of Gloucester. If you saw the movie, A Perfect Storm, the doomed boat left from there. During the actual storm (11/1/91) I remember commuting back from work on the MBTA “purple” train line. When we got to the causeway in Salem, it seemed that the water was as high as the rail tracks, that we were in fact rolling on water. When I got home wind and cold salt spray were everywhere, even as far as our house, which was a good 1/4 mile back from the beach. Winters in Rockport could be hellacious.

Mostly though, it was idyllic. In nice weather, tourists arrived and strolled down past our house to get fudge, lobster, t-shirts, and maybe a nice watercolor painting. You could do it as a day trip because of the commuter line. One day the guy from J. Geils walked past. I nodded at him, pretending to be one of the flinty Cape Ann locals who had been on the island since the 1600s.

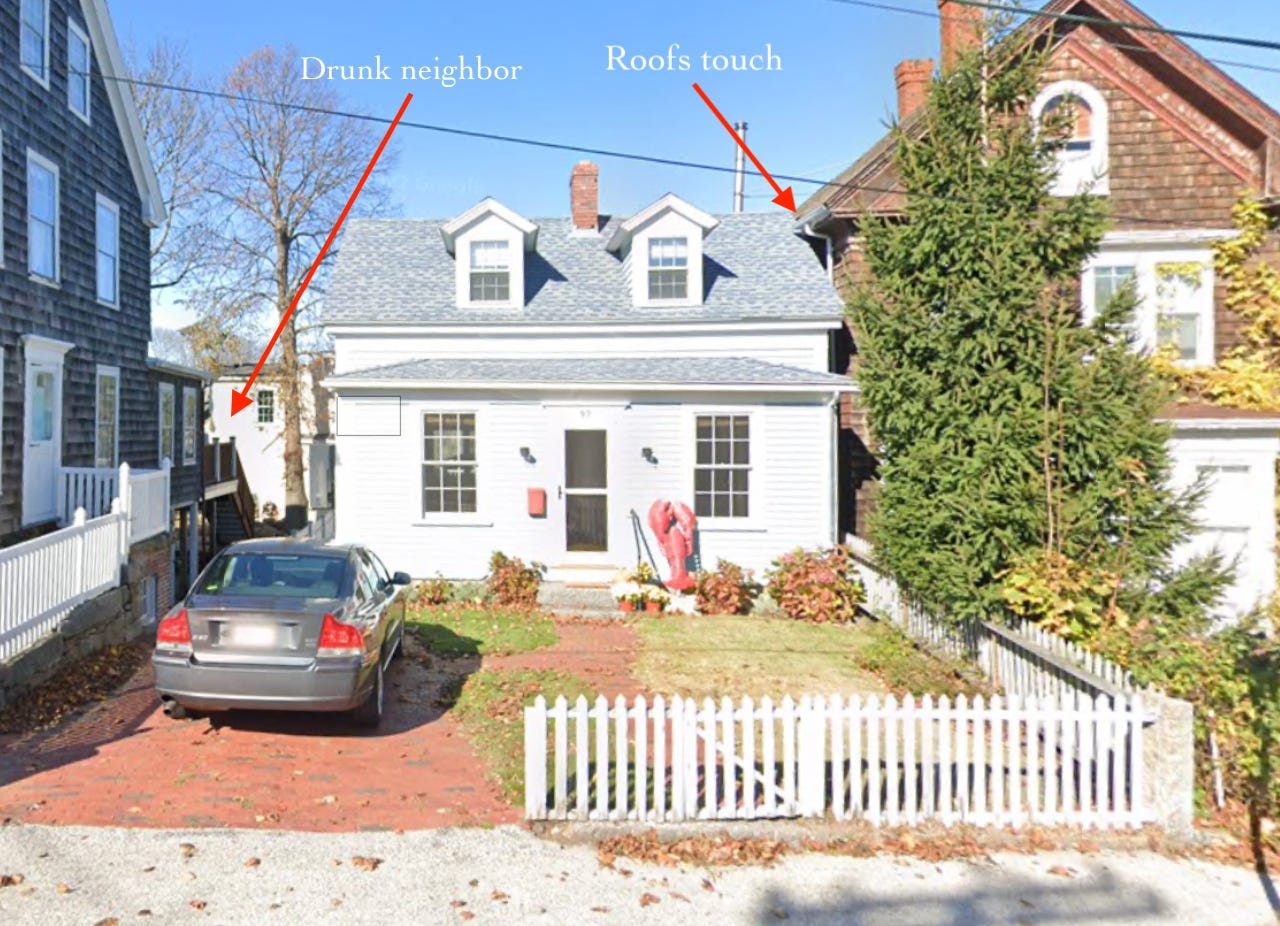

These locals were colorful. On one side of our house lived a legitimate sea-captain, who was holed up in a basement that met no kind of code. It was a hovel. One day I heard a noise coming from within, and peeking in the dirty window saw him sprawled on the floor, moaning in pain. When the ambulance came, they said “How much did you drink this time, Bob?” “As much as I could.” Liquor stores would make regular deliveries with boxes. My wife would yell at the drivers, to no avail. I remember in particular the smell of apricot brandy. Eventually he moved to a better situation.

I was told that there were Cape Ann locals who had never been to Boston, a simple train ride, but who had roamed far and wide in their fishing boats, all the way to maritime Canada. Such was the supposed insularity of the place. I think it was true to a certain extent, but we made friends easily enough. Some were locals; some weren’t.

In our neighborhood, the houses were close. Our rooftop actually leaned over and touched the roof of the next house. When we bought I asked the agent about it and he pointed out that the houses had been holding each other up for quite a while. So I accepted it. Tourists would point it out and I would pretend to be shocked.

Anyway, the point is that I commuted on the train, which was a long ride. Walk to the train, ten minutes. An hour and a half to North Station. Then the green line to Government Center. Change to another Green Line to get off on Comm Ave. The Green Line trains are glorified trollies. I would get home late.

A defector

One day I was trudging up to the train when a man pulled over in a small red pickup. He asked me, in an Eastern European accent, whether I wanted a ride to work. It was “Larry Martin.” I said yes, and we had a nice chat on our way in.

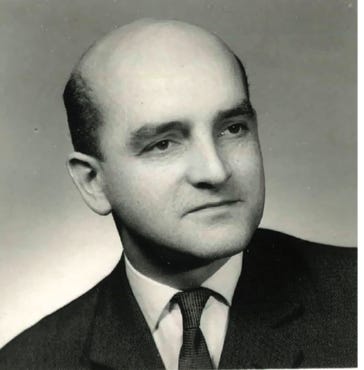

Who was Larry Martin? I had seen him around the halls of COM. He was a completely bald, somewhat powerfully-built guy, with an unmistakable accent. He could have been a Bond villain, except his demeanor was always sunny and friendly. He wasn’t in my department, so I didn’t know him that well. But I did know that he was one of the odd (to me) sorts of academic hires that COM was known for at that time.

For instance, our dean was someone who had defected from East Germany, an ideologically-compatible figure for then-president John Silber. Under Joachim Maître, COM became involved in programs educating Afghan journalists that were controversial. Maître ran a center for defense information (“propaganda”?) and also taught in the IR program. To the extent that Maître even knew how I was, he was nice to me. When I met him, he informed me that my $28,000 salary would be augmented by $2,000 when my dissertation was complete. Two weeks later it was done ( I was really just waiting for the paperwork), so I went back to tell him. He seemed a bit surprised, but just shrugged and congratulated me.

Maître was later caught up in bit of a scandal when he plagiarized a graduation speech. I saw it in the morning paper at the Rockport train station. I also remember, but I can’t find the video, that I was sitting behind him during the speech and so saw myself later on the evening news.

This led to a memorable event where Silber came to our faculty meeting to determine what would happen. Silber was to me a truly scary person. I would compare him to the man-with-no-eyes from Cool Hand Luke. You could not look straight at him. I had been involved, stupidly, in some faculty senate politics, and I thought (ridiculously) that maybe I was on some sort of enemies list. Silber said that Maître would step down as dean, and retain his faculty position. Then, basically glaring at everyone, collectively and individually, he asked for a vote. We all voted unanimously to accept the wise decision, although one person (not me) bravely “abstained.”

Still, I liked Maître. Later he was on a defense committee for a student doing a thesis about acid rain, which is a function of smokestack emissions. He spewed cigar smoke during the meeting while his colleague belched out the same from his pipe. It was the 90s… I came back to BU in the 2000’s. Maître semi-recognized me, and we still got along fine.

Larry Martin

“Larry” was also a defector, from Czechoslovakia. As I learned soon upon arrival at COM, he had been in the Czech version of the KGB, and defected after the Prague Spring. He was targeted with the death penalty back home, and now was at BU as an expert on “disinformation.” This was well before the profusion of “experts” on disinformation that we now see; back then the name carried a specifically Soviet connotation and a connection with other spy-tools such as “active measures.” It seemed clear to me: If there is an expert on propaganda, he is it. And he met the qualifications that I outlined above: He had done it for real but rejected it.

Larry was in fact Ladislav Bittman. Sometimes I would see his name as Martin-Bittman. We called him Larry.

So on a cold day, Ladislav Larry Martin-Bittman was pulling over in a modest red pickup to offer me a ride over the Tobin Bridge to work. I couldn’t turn that down, and it was a chance to get to know him. These rides occurred sporadically, basically whenever he saw me walking up to the train and our schedules coincided. We didn’t become car pool buddies, but it happened often enough to have a nice relationship. The rides focused on two things: life in Rockport and more generalized shop talk.

Naturally I could not resist asking him about spy stories. One that I remember was: What was his first “assignment”? He said that he had been assigned to meet someone in a “ranger uniform” at the train station. He waited. No ranger. After a longish wait, finally a whole crowd of people came in wearing ranger uniforms. Larry: “I considered this a monstrous provocation against me.”

At BU, Larry was running a Program for the Study of Disinformation, which I think was mainly a one-man thing. There were printed outputs, and I had some that I used in my course. I can’t find them now. They are in the archives at BU, but only in print. Also Larry had done a few books, and these provided valuable stories that could show students about the specifics and the mechanics of disinformation in those post-Bond days. Forgeries, front groups, and some other things that must have just been done for the fun of it.

The story that has been reported most widely about Larry was a caper where he planted some incriminating documents at the bottom of a lake, and then “discovered”them, in full scuba gear, for television cameras. The docs indicted some West German officials as former Nazis. It was called Operation Neptune.

The great battle in journalism education is practice vs. theory. Larry was more focused on practice. He noted that he had lived through every press system, and that was enough for him to know what worked. He tolerated my academic opinions graciously, but I did not often seek to contradict his views with study results or theories. Indeed, when I told him that I was teaching a course in propaganda, I could sense that he was thinking, “what the hell does this kid know about it?” In any case, we agreed about a lot of things. A shared distrust of authoritarianism and its effects on journalism was one key to a good friendship.

Nowadays if you Google “disinformation” at BU you don’t find so much about Larry. There are programs on “climate disinformation,” and COM has misinformation academic experts who focus mainly on transgressions against progressive politics. The current crop of scholars might have found some common ground with Larry in the idea that Russians interfere in elections, but I suspect he would not have had much use for how we currently treat these concepts in our communication field.

When a craze over the effects of propaganda came after World War I, social scientists were quickly able to give birth to the field of studying media effects, empirically and scientifically. That’s what I do too, but I have to admit that I’m always a tiny bit skeptical about some of our grander claims. The promise of the propaganda-inspired research was that there could be a truly scientific theory of persuasion, which of course we do not have. When people say that figures like Goebbels did propaganda “scientifically,” I think it’s a huge overstatement. Sure, they used techniques and strategies, but when you can back up your message with physical violence, we don’t necessarily need science to understand it. To be more diplomatic about it, I think that with a topic like propaganda, the work of historians will be just as useful as that of social scientists in helping us to come to grips with it. I’d say the same thing about the current focus on disinformation. I don’t expect social science alone to give us the right answer about how we should now control speech in the face of these modern forms of propaganda.

One of the things I learned from Larry, and a few other well written books on propaganda techniques – especially those pioneered in the Soviet union – is the reliance on journalists to be conduits for disinformation. Typical techniques such as forgeries, front groups, fake political alliances and other strategies work best when they can be disseminated within a free journalism system. It is an Achilles’ heel of journalism, unfortunately, that there is an attraction for good stories, for compelling narratives, and even more unfortunately, for narratives that align with the ideological priorities of journalists. Both our own native journalism and foreign state-run propaganda focus on our western weaknesses, which is why racial tension can so easily be a feature of anti-American propaganda. It is an open sore that is easily picked at. Ellul, among other authors that I use in the class, point out that propaganda is often true, or may even be most effective when it is true.

Art colony

Back in Rockport, Larry was a good friend. He had us over to dinner at his house with his wife or girlfriend (sorry I don’t remember which; she was lovely) and I learned about his interest in painting. The main style of painting in Rockport, with the many artists that live there in an artist colony, were oils and watercolors of the waterfront scene. One artist that we knew a little bit was named Liné Tutwiler. She and her husband had a gallery on Main Street. One year they gave us a small Christmas ornament for our daughter that she had painted. Later we bought a painting that she had done of our house with two other houses. When we sold the house the new buyers wanted the painting, understandably, and so we let it go. I thought she was a very good artist and I wish we still had the painting.

Larry’s style was much different. I would call it folk art. The colors reminded me of things you might see painted on an Easter egg from one of the eastern European countries. In the late 2000s I came back to BU for a second stint at COM. Now I was the associate dean. Things had changed somewhat. Silber was gone. A more normal academic order seemed to be in place. Larry was retired, but he came in one day and we were able to reminisce. We talked a little bit about having an exhibition of his paintings, which would’ve been nice. Unfortunately before the planning for that was completed, I left for Indiana.

In the painting above, Larry depicted the famous Motif #1, the Rockport shack that is supposedly the most-painted object in the world. One time Larry invited me to go fishing with him. I took a look at his boat which was tiny, like the boats in the picture. I elected not to go.

When I left Rockport in 1994 Larry told me “you will return.” He had a strong belief in the power of that particular village. We haven’t yet returned, but I wouldn’t rule it out 100%. It was a great place to raise our daughter and we knew some very interesting people there. Amongst them Larry was one of the most memorable.

Nowadays I think of how words like disinformation are used, a word whose meaning Larry played a key role in communicating to the American public. Things have changed a lot, especially in the way that there’s been an ideological reversal around the word. Then, it was something “they” did to “us.” Now, it’s something we do to each other.

I think that Larry was an American patriot, like most of the people I’ve met who lived previously under communist rule in eastern Europe. He became more American than the Americans. A true New Englander as well.

I also wonder about the things that Larry might’ve done that we won’t know about in his role as a communist spy. Was anyone hurt physically? I never asked him. Certainly it was part of his job to destroy peoples’ reputations. In his Times obit, he’s quoted as saying “I openly admit that I did a lot of damage to the West, particularly to the United States, as a specialist in dirty tricks.” I’m also aware that, of course, there are people doing similar things on our behalf, running secret operations and active measures in who knows how many ways. When it’s for us, it’s not a crime.

Larry Martin could be a valued commentator about propaganda in the 60s and 70s precisely because by the 80s and the 90s things were changing. He had played a part in the era historically, the facts of it became clear, and then he created a role where he could comment honestly, revealing to us that propaganda is not a science as much as it is a craft. What he would say about today’s craft would interest me.

We are soon going to have a better understanding of what disinformation and misinformation are today, and the role that they have played in issues such as the COVID epidemic, election interference, and other such issues. It seems likely to me that social science, while it can provide many useful hints, will never provide a theory or law-like understanding of organized lying. If research gets close, the liars will adapt. Our particular mania over misinformation and disinformation will come to a close much as the previous era of mania over propaganda came to a close. When select individuals emerge from behind the scenes who participated in these events, and find themselves in a position to comment honestly, we will come to know more, when accurate history replaces the journalism that is corruptible by dirty tricks. Social science, with its present-day perspective, will then surely be partially redeemed in some of its findings, but much will also fall back as chaff.

New York Times obituary about Larry.

A Facebook page with many photos and examples of Larry’s art.